Overview

Trade issues are once again in the headlines with the re-election of President Trump and his promise to immediately impose up to 60 percent additional tariffs on imports from China.  For U.S. companies—and those whose supply chains are tied to China and have significant import sales in the U.S.—these threats and their potential impact cause significant headache.

For U.S. companies—and those whose supply chains are tied to China and have significant import sales in the U.S.—these threats and their potential impact cause significant headache.

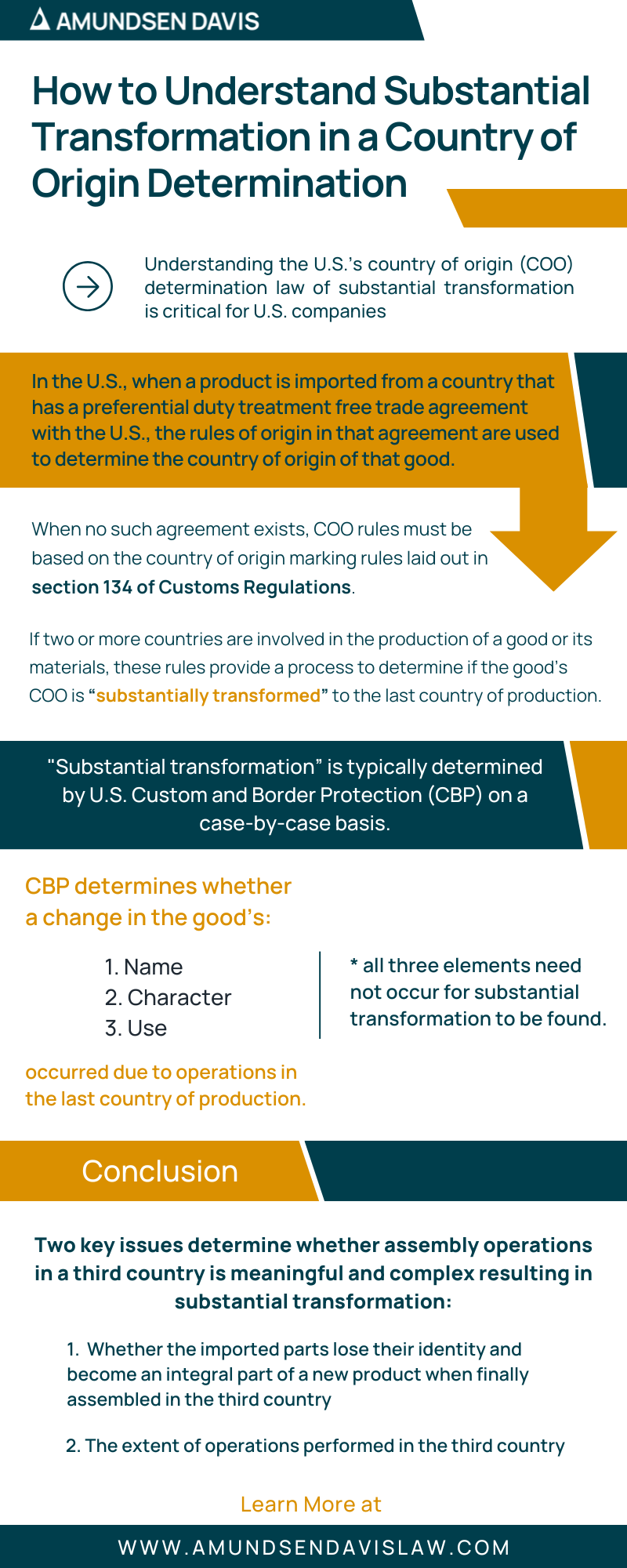

Fortunately, shifting supply chains out of China provides a viable solution to this problem. As a result, understanding the U.S.’s country of origin (COO) determination law of substantial transformation is critical.

[Infographic] How to Understand The Law of Substantial Transformation

Law of Substantial Transformation

In the U.S., when a product is imported from a country that has a preferential duty treatment free trade agreement with the U.S., the rules of origin set out in that free trade agreement must be used to determine the country of origin of that good. In scenarios where no such agreement exists, COO rules must be based on the country of origin marking rules laid out in section 134 of Customs Regulations. These rules provide a process to determine the COO if two or more countries are involved in the production of a good or its materials so the good’s COO is “substantially transformed” to the last country of production.

Typically, “substantial transformation” is determined by U.S. Custom and Border Protection (CBP) on a case-by-case basis. CBP examines the totality of circumstances to determine whether a change in the good’s name, character, or use occurred due to the manufacturing or processing operations in the last country of production, although all three elements need not occur for substantial transformation to be found. The analysis determines whether the “parts lose their identity and become an integral part of a new product.” Assembly operations that are “minimal or simple,” as opposed to “meaningful or complex,” generally will not result in a substantial transformation.

Although no single factor is dispositive CBP uses the following factors to evaluate whether an assembly operation is “meaningful or complex” enough to constitute substantial transformation,:

- The number of components assembled,

- The number of different operations,

- How time-consuming the operations are,

- Skill level required for operations,

- Attention to detail required,

- Value added to the article,

- Overall employment generated by the manufacturing process,

- Resources expended on product design and development,

- Extent of post-assembly inspection and testing,

- Nature of post-assembly inspection and testing, and

- Origin of components.

Single Country Originating Parts

One issue of note involves a scenario where a significant percentage or all of a product’s parts originate from a single country, but are further processed or assembled in another. While I found no case or rule addressing COO determination under this specific circumstance, CBP’s reasoning and decision in H270580 (May 10, 2016) provides some guidance. In H270580, CBP was asked to issue a final determination concerning the COO of two pieces of exercise equipment. The first scenario involved importation of all parts from China and then welding, painting, and assembly in the U.S. The second scenario was similar to the first, except that some of the sub-assemblies were welded together in China.

In its analysis, the CBP found the extent of U.S. assembly operations—which included welding, cleaning, degreasing, grinding down, spraying with paint, and assembling—to be sufficiently complex and meaningful to result in substantial transformation. Further, the operations in the U.S. required significant education, skill, and attention to detail. In the second scenario, however, CBP found the “components that together imparted the very essence of the finished product were imported as pre-assembled.” As a result, the CBP found the processing in the U.S. did not result in a substantial transformation.

Conclusion

Based on H270580, two key issues can be reasonably concluded to be dispositive in determining whether assembly operations in a third country is meaningful and complex resulting in substantial transformation:

- Whether the imported parts lose their identity and become an integral part of a new product when finally assembled in the third country; and

- The extent of operations performed in the third country.

Regarding the extent of operation in the third country, the analysis factors are whether:

- The “essence” of the imported component change due to assembly operations there, and

- The product requires significant additional work to create a functional product for commerce.